Over 6,000 miles east of North Carolina lies Bioko Island, an island rich in both culture and biodiversity and part of the only Spanish-speaking country in Africa. Unknown by many, this island is part of Equatorial Guinea in West Africa, located approximately 20 miles off the coast of Cameroon. Dotted with deep crater lakes, cascading waterfalls, towering volcanic peaks, lush tropical forests, and expansive black sand beaches, Bioko Island harbors seven rare species of monkeys and four species of endangered sea turtles, along with unique insect and bird species, some still yet to be discovered. This biologically significant island provided the backdrop for Gretchen Stokes’ semester abroad during the spring of 2011.

Gretchen is a junior in the Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology major at NC State University, and she says that she knew from the start of her college career that she would participate in Study Abroad, though she recalls, “I never dreamed it would take me halfway around the world to Africa!” Gretchen stumbled upon the program while gathering information for the Conservation Biology Concentration Task Force in her major. Organized through Drexel University in Philadelphia, the Biodiversity on Bioko Island study abroad program is a collaboration of Drexel University, the Universidad Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial, and the Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program. It is a hybrid program that combines four to six weeks of field courses with six weeks at a small university and incorporates five courses totaling 15 credit hours, all transferable to NC State University.

Gretchen is a junior in the Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology major at NC State University, and she says that she knew from the start of her college career that she would participate in Study Abroad, though she recalls, “I never dreamed it would take me halfway around the world to Africa!” Gretchen stumbled upon the program while gathering information for the Conservation Biology Concentration Task Force in her major. Organized through Drexel University in Philadelphia, the Biodiversity on Bioko Island study abroad program is a collaboration of Drexel University, the Universidad Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial, and the Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program. It is a hybrid program that combines four to six weeks of field courses with six weeks at a small university and incorporates five courses totaling 15 credit hours, all transferable to NC State University.

Here is Gretchen’s fascinating account of her experience abroad:

My Semester in Equatorial Guinea

by Gretchen Stokes

My studies on Bioko Island began with a two-week expedition to the undisturbed Gran Caldera Scientific Reserve, a hollowed volcanic crater encompassing nearly one-third of the island, covered with dense rainforest and abundant wildlife. A team of scientists, students, volunteers, porters, and local guides trekked deep into the rainforest, hiking two days to reach base camp. Here, I conducted surveys on monkey populations and studied methods in field ecology using the most advanced scientific technology. I worked with the team to photograph and record vocalizations of the troops of monkeys we encountered in hopes to better convey the importance of their conservation.

The island’s monkey populations have been declining since the increase in hunting activities in the 1980s as well as increased accessibility to the forest from newly developed roads and increased demand for monkey meat in the market. The team of scientists is now examining exactly how these human interactions are affecting populations of monkeys over time. Currently, three of the seven species of monkey are listed as endangered and one, the Pennant’s red colobus monkey, is listed as critically endangered. By performing an annual census and recording population data, the goal is to work with the local government towards conservation regulations and hunting bans in the vulnerable forests.

While on the southern end of the island, I worked with Equatoguinean students on a sea turtle research team, surveying the beaches through the night and into the early morning. I witnessed nesting sea turtles as well as poaching camps and evidence of hunted sea turtles. The data I collected on the nests and tracks will play an important role in the ongoing study of the island’s turtles and the conservation of all four sea turtle species.

While on the southern end of the island, I worked with Equatoguinean students on a sea turtle research team, surveying the beaches through the night and into the early morning. I witnessed nesting sea turtles as well as poaching camps and evidence of hunted sea turtles. The data I collected on the nests and tracks will play an important role in the ongoing study of the island’s turtles and the conservation of all four sea turtle species.

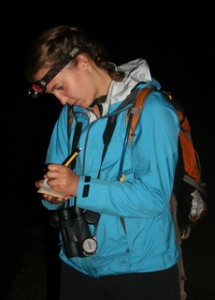

Following the conclusion of that expedition, I traveled to the small village of Moka, in the island’s highland forests, where I studied island biogeography in the context of species diversity and evolutionary development. Each student designed and conducted an independent research project and was advised by Dr. Tom Butynski, one of the most recognized primatologists in Africa. I chose to conduct independent research on the habitat preference and distribution of four species of galagos, which  are small primates also known as bushbabies. My work was entirely during the evening hours in order to conform to the galago’s nocturnal nature. During my field time, I worked with local guides and Equatoguinean students, which allowed for an excellent opportunity to improve my conversational skills in Spanish as well as learn about the villagers’ views of these animals.

are small primates also known as bushbabies. My work was entirely during the evening hours in order to conform to the galago’s nocturnal nature. During my field time, I worked with local guides and Equatoguinean students, which allowed for an excellent opportunity to improve my conversational skills in Spanish as well as learn about the villagers’ views of these animals.

I recorded data on habitat preference in relation to elevation as well as opportunistic observations of unique galago behavior. I also experimented with behavioral changes to audio playback. Most notably I observed unique galago behavior and discovered a species of bird potentially new to the island. It is exciting because this research proved valuable not only to the island’s data collection but also to the greater world of science.

I recorded data on habitat preference in relation to elevation as well as opportunistic observations of unique galago behavior. I also experimented with behavioral changes to audio playback. Most notably I observed unique galago behavior and discovered a species of bird potentially new to the island. It is exciting because this research proved valuable not only to the island’s data collection but also to the greater world of science.

I returned to the capital city of Malabo, where I attended classes at the Universidad Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial. These classes included Natural Resource Economics, Society and the Environment, and Advanced Spanish Language. My time in the city was an immersion in the Spanish language and the unique African culture. I feel that my abilities in the Spanish language are much improved, as I became conversational in the language and was able to communicate fluidly with the local people. Not only did I speak Spanish, but I also began to learn the languages of the indigenous Bubi and Fang ethnic groups. I studied the social and cultural implications of the two groups and how these impact the government and politics in Equatorial Guinea. I took salsa dancing lessons, attended cultural performances, went on field trips to nearby natural areas, and met with oil companies, including workers at Exxon Mobil and Marathon.

One of the most important aspects of my studies was learning about the oil industry on the island. Four oil companies prosper from offshore drilling and I had the opportunity to visit the oil company compounds, meet with oil workers, and explore the relationship between the government, oil companies, and local people. Because of the recent economic boom from oil production, the demand for bushmeat has also increased. Bushmeat includes any wild animals hunted from the forest, most commonly snakes, antelopes, monkeys, and other small mammals. Visiting the local bushmeat market was a sobering experience for me after seeing wildlife flourishing in the rainforest just weeks before.

I made it a priority to be involved in service activities while in Equatorial Guinea. Most notable was providing environmental education for elementary-aged children at a local school. My lessons, spoken completely in Spanish, strived to inform students about topics such as pollution, habitat destruction, and human impact on the environment. None of these kids have ever left the city, let alone the island. They do not know more than what they see in a few city blocks. They are not aware of the connection between humans and the environment nor do they know of the biodiversity found in their country.

Not only did I gain a wealth of knowledge and appreciation of the culture, but I also have a newfound appreciation for the profound impact that education can have. Education is vital, the foundation of how to create a positive change in the world. It can empower people and change the way they live. Through my service work, I have discovered my passion for education. I know now this is what I am called to do.

Not only did I gain a wealth of knowledge and appreciation of the culture, but I also have a newfound appreciation for the profound impact that education can have. Education is vital, the foundation of how to create a positive change in the world. It can empower people and change the way they live. Through my service work, I have discovered my passion for education. I know now this is what I am called to do.

My study abroad experience was enriching, fulfilling and empowering, and it truly captured the essence of my field of study. From the tiniest butterfly to the beautifully majestic sea turtles, I witnessed nature’s incredible diversity, interconnectedness, and resilience. I witnessed our natural environment undisturbed, in its most raw form.

Following my studies in Equatorial Guinea, I decided I was not ready to leave Africa! I flew to East Africa to travel around Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. I ventured into northern Kenya’s vast hills dotted with giraffes, elephants, zebras and rhinos, and I toured one of Jane Goodall’s chimpanzee rescue centers, meeting with scientists from the Mpala Research Reserve. I continued west to hike Kenya’s tallest waterfall, Thompson’s Falls, and camped in a nearby village.

I then proceeded to Jinja, Uganda, where I whitewater rafted down the Nile River and bungee jumped 145 feet above it. I traveled with a local woman across Lake Victoria to a rural village, helping her with agriculture education, handing out seeds and instructing the villagers on how to raise their crops more sustainably with a greater yield. We also supplied Jinja’s children’s hospital with much needed medical supplies and food. I was overwhelmed as I walked through the crowded rooms of undernourished children. I remember when we gave a child a mosquito net, his mother told us her husband had just died from malaria and her son was sick with malaria because they could not afford a net. I will never forget the small smile the boy mustered as we hung the net above him.

After leaving Uganda, I made my way to Tanzania for a six-day safari to parks including Serengeti National Park and Ngorongoro Conservation Area. I watched lions wrestling in the golden grasses, thousands of wildebeest galloping across the savannah, a leopard sinking his teeth into his latest catch, and elephants trumpeting calls to one another. When you think of Africa, this is what you imagine. Each day brought something more breathtaking than the last, from the wildlife to the sunsets. I even participated in a ceremony with the indigenous Maasai people and indulged in a village’s traditional foods.

The last destination in the journey was to the Zanzibar archipelago. I spent a few nights in historic Stone Town and then at the secluded beaches on the Indian Ocean. This gave me time to reflect on my experiences in Africa and how to best apply these lessons learned upon returning to the United States. Traveling around Africa gave me a better perspective on how much there is to see in the world and it taught me how to make the most out of every day. From day to day choices, such as the food I eat and the music I listen to, to the long-term decisions I make, such as my plans after graduation, my life has been changed.

- Read Gretchen’s Travel Blog

- More About the Biodiversity on Bioko Island Study Abroad Program

- More About CNR Study and Work Abroad Opportunities

About Gretchen Stokes:

Gretchen Stokes, of Apex, NC, is a junior in the Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Biology major with a minor in Spanish. Gretchen is a College of Natural Resource Student Ambassador and is a Class of 2013 Park Scholar. Park Scholarships are very prestigious, full, four-year, merit-based awards for exceptional NC State University undergraduate students. Following graduation, she plans to pursue a graduate degree through the Peace Corps’ Master’s International Program and later work toward a PhD degree. Gretchen hopes to ultimately work for an organization like the United Nations Environmental Programme, NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, or the Natural Resources Conservation Service.